What is a clinical trial?

All new drugs and treatments are thoroughly tested before they’re made available to patients. Following tests in a laboratory, they’re tested on people. Research studies involving testing new drugs and treatments on people are called clinical trials.

Why are clinical trials important?

Clinical trials are important, because they’re the only way to develop new treatments – and improve existing ones – for you and other people with blood cancer. Researchers can compare the effects of new drugs and treatments to find out whether they work better than the current treatment used.

Clinical trials may test:

- new drugs that have passed safety studies

- medical equipment

- new combinations of current treatments, and

- different ways of giving treatments.

The goal of clinical trials is to find better and kinder treatments for people with blood cancer.

Although the outcome for people with blood cancer continues to get better, there’s still a lot more to be done to improve treatments and quality of life.

Clinical trials are also important to find out:

- whether new treatments are safe

- what side effects a treatment may cause (and how to manage them).

If clinical trials aren’t carried out there’s a risk that people could be given treatments that don’t work or are harmful.

This is blood cancer: clinical trials

How clinical trials are funded and planned

How clinical trials are funded

Clinical trials in the UK are mainly funded by the government, drug companies and charities.

All trials, no matter who funds them, are checked and monitored in similar ways to make sure that everyone involved is protected. Each trial also has a sponsor who is responsible for running the trial. The sponsor may be the organisation funding the trial or the institution hosting the research (for example, a university or a hospital).

How clinical trials are planned

Once a group of researchers have an idea, they need to develop a protocol.

A protocol is a detailed plan for the trial, which includes:

- why the trial should be done

- the number of people involved

- who should be able to take part in the trial (this is called the eligibility criteria)

- details of the treatments given in the trial

- what medical tests people will have and when

Everyone involved in the trial must use the protocol. This keeps the people taking part safe and makes sure that the results of the trial are reliable.

How patients are kept safe

Every new treatment carries some risks, but the overall aim of a trial and the researchers is to reduce these risks for you. If at any stage the risks of the trial are greater than the benefits for you, the trial will be stopped. To keep you safe, all trials are monitored by the following groups.

The MHRA is a group of the Department of Health that makes sure the safety and quality of the treatment tested in a trial meets good practice standards.

Research Ethics Committees are groups run by the NHS Health Research Authority. They are independent groups of people including doctors, nurses, other medical staff, members of the public and sometimes lawyers. The group makes sure that your wellbeing and rights are protected. They also make sure that the information you are given tells you everything you need to know and is easy to understand.

These are national and local groups in your hospital or research centre that make sure that the trial is planned well and carried out safely. They also check that the trial is based on scientific knowledge and follows national guidelines and safe practices.

Giving consent

Consent is when you give your permission to have any medical treatment, test or examination.

Before giving your consent, you’ll be given a patient information sheet, which includes detailed information about the trial to help you decide whether you want to take part. You can also keep this to refer to during the trial.

Understanding the complex information to enrol can be overwhelming but our Clinical Trials Support Service is here to help you navigate through the entire process – whether you're a patient, carer or healthcare professional.

Once you’ve decided to take part in a clinical trial, you’ll have to give your informed consent and sign some forms.

These forms are important legal documents that protect both yourself and the organisation running the trial.

Before you give your consent, your trials team will discuss the trial in detail with you, the tests you may need, the frequency of your hospital visits and any known benefits, risks and side effects of the treatment. They will also discuss alternative treatments and options with you so you know about all of the options before making a decision. It’s important that you ask any questions that you might have.

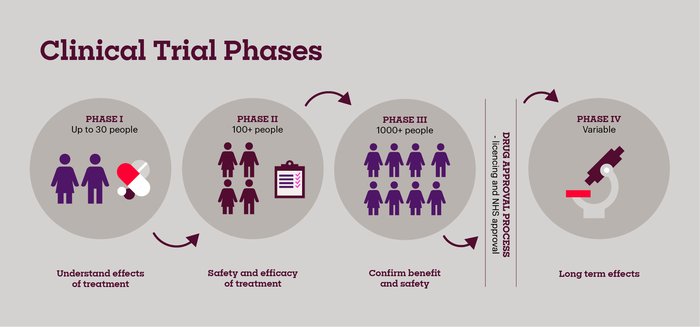

Clinical Trial Phases

Pronounced Phase "one", these trials test the safety and side effects of a new treatment. People who take part in phase I trials (up to 30 people) often have advanced cancers and have usually tried all the treatment options available to them. The first few patients to take part in the trial are given a very small dose of the drug. If they respond well, the next group have a slightly higher dose. The dose is gradually increased with each group. The researchers monitor the effect of the drug until they find the best dose to give. This is called a dose escalation study.

Pronounced Phase "two", these trials test the new treatment on a larger group of people (more than 100) to find out more about the side effects, safety of the new treatment, and the effects on the cancer. These trials can last several weeks or months, and sometimes they can continue for years if the person is responding to treatment.

Pronounced Phase "three", these trials involve more people (hundreds or thousands) and compare new treatments with the current treatment available longer-term.

Pronounced Phase "four", these trials trials are carried out after a new drug has been shown to work and has been licensed to be used (a licence means the medicine can be made available on prescription). These trials aim to find out how well the drug works when it’s used on more people, the long-term benefits and risks, and more about the possible rare side effects.

Clinical trials are divided into phases. The early phases look at the safety and the side effects of a new drug. Later phases test whether a new treatment is better than existing treatments.

Types of clinical trials

In open label trials, both you and the researchers know the treatment you’re having. These trials usually compare two very similar treatments to test which treatment is the best, and usually happen in the early phases.

If you take part in a randomised clinical trial, you’ll usually be put randomly into either:

- the treatment group – where you’ll be given the treatment being trialled, or

- the control group – where you’ll be given the existing standard treatment, or a placebo (a treatment that has no effect) if no proven standard treatment exists. A placebo is only used if outside of the trial, there is no other treatment option available. This could be because the person has already tried all the available treatments. Nobody in the trial would be given a placebo if there was any other treatment option available to them, as this would be unethical.

If you take part in a randomised trial (most phase 3 and some phase 2 trials are randomised) a computer programme is usually used to randomly select which group you will be in. Your personal details, such as age, sex and state of health, are taken into account so that the groups in the trial are as similar as possible. This helps to make sure that the results of the trial are reliable and accurate.

A blind trial is a trial where the people taking part don’t know which treatment they are getting. You might get the new treatment. Or you could receive the standard treatment. So that you can’t tell which treatment you are having, everyone taking part will receive identical injections, tablets, or other forms of treatment.

In a double blind trial, you won’t know which group you’re in, and neither will the researchers, until the end of the trial. This makes sure that the results are more reliable as they will not be influenced by your expectations or the researchers’ expectations.

Hear the team bust the myths

Our Clinical Trials Support Service team talk through some of the common myths you may have heard about clinical trials.